In the first instalment of the History of the Suit, to celebrate the launch of our Made-to-Measure range, we considered the influence of key individuals, Charles II and Beau Brummell, who both had a significant impact on the lounge suit we know today. We looked into how the industrial revolution and the introduction of machinery - allowing for mass production and distribution of garments - clothed a burgeoning middle class. This period also created the businessman, who needed to dress accordingly, often in dark and sombre colours and style. We ended Part I with the Victorian era’s contributions to men’s fashion which included the introduction of the shirt, its associated stand-up collar and the proliferation of tie.

It was the dawn of a new century, and the Victorian era came to an end with the death of Queen Victoria in 1901. Her son Edward VII ascended to the throne.

By the beginning of the 20th Century frock coats and morning coats' popularity began to decline. The lounge suit which had been considered very informal, worn at the seaside, slowly increased in availability around town. By the end of the first World War, lounge suits became commonplace, with morning coats being reserved for very formal daytime wear. North America adopted a lot of the developments in men’s suits and soon did away with full dress tails for evening wear, opting instead for the short dinner jacket.

To Turn-up or Not

The development of trousers made – excuse the pun - strides in the early 20th Century. Another royal fashion footnote comes from Queen Victoria’s eldest son Edward Prince of Wales who introduced the cuff (turn-up) to the trouser hem, initially to keep one’s trousers out of the dirt. Later, men opted for straight-legged trousers with bottoms (or cuffs) measuring a generous 23 inches; today’s average is between 16 to 20 inches. Trousers were high-waisted, and creases appeared in the 1920s.

Royal beginnings: the not so humble turn-up

After the great war, narrow cut single-breasted (SB) jackets were now in vogue; a look popularised in F.Scott Fitzgerald’s classic The Great Gatsby (published in 1925). Unlike today, where most SB jacket lapels are notched, in the 1920s, lapels were peaked and were often wide. These new fashionistas did not dispel the double-breasted style entirely; it was fashionable to wear a double-breasted waistcoat under one’s single-breasted jacket.

By the 1930s and 1940s, three-piece suits were very much part of the fabric of business life. However, in the 1930s two remarkable developments took place: suits became roomier, unlike the tight fitting 20s, and it was the first time men began mixing & matching jacket and trousers colours and cloths.

Why this occurred is difficult to pinpoint. It could be down to the yo-yo nature of fashion (like music). After a period of a particular kind of style, there appears to be a fit of pique, followed by a lurch to, more often than not, an opposite view.

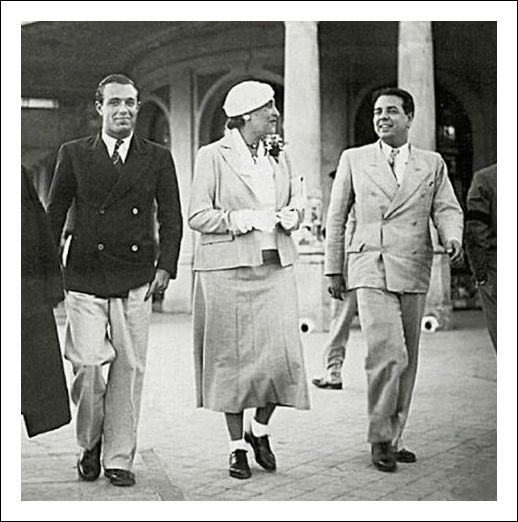

Writer Jorge Luis Borges (left) in 1937

The result, however, created a more masculine presence and an accentuated athletic form with broad shoulders, narrow waists and full legs now being the norm. An article in the Vintage Dancer website goes on to add that:

Suits were cut to add the illusion of both height and width. Jackets were long with wide padded shoulders and lapels. The double-breasted suit was especially good at adding width. Both single- and double-breasted remained popular throughout the entire decade.

With regards to mixing and matching of suit garments, this could be the result of the depression in North America with men, short on funds for new clothes, hoping to give the impression of a more extensive wardrobe. Unwritten rules dictated that darker colours were on top (the jacket) with lighter hues for the trousers (or pants). If a pattern was worn, top or bottom, a solid colour colour would be worn with. Please visit the Vintage Dancer website to view some wonderful 1930s fashion illustrations.

Thank You for the Music: Its Impact on the Lounge Suit

After World War II, something else started having an impact on men’s fashion which had not occurred before, music. With the advent of bebop jazz in the 40s styles continued to loosen illustrated here by Charlie Parker.

Charlie Parker & Miles Davis at The Three Deuces, New York 1947

By the 1950s, men’s fashion and music coalesced even further with rock n roll duck-walking on to the world’s stage. In response to this new wave of edgy sound, the Teddy Boy was born in London in the early 50s. Sartorially, they adopted for the unlikely combination of 1940’s American zoot suit and working-class Edwardian styling which included loose jackets and tight trousers often exposing the socks. It is from these influences they took their name with the British newspaper The Daily Express, in a headline, shortening Edwardian to Teddy. Up to until the 50s, formality and conservatism dictated the progress of the suit. The Teddy Boys though, and the emergence of youth culture, changed that forever. It was no longer about business or evening wear, it was about rock n roll.

Mod pioneers, The Small Faces in 1965

"Fashion-obsessed and hedonistic cult of the hyper-cool."

Further illustrating the power and reach a small group of people can have at a national and global level, the Mods, came into being again in London, in the late 50s. Along with other elements, amphetamines and scooters, they made the early to mid-60s their own, imprinting their style and music on the decade. Design academics, Paul Jobling and David Crowley called the mod subculture a "fashion-obsessed and hedonistic cult of the hyper-cool"

With its origins in modern jazz and the beatnik culture, they brought a smoothness and sophistication to their dress. To truly realise their unique sense of style, their suits were tailor-made in a slimmer cut. Lapels were narrow, ties were thin, and collars were buttoned down. Furthermore, in a striking example of paradox to break away from the traditional, they adopted its very icons in the British flag and The Royal Air Force’s roundel in their dress.

Royal Air Force roundel & Mod symbol

So popular was the Mod look, it was not long before the look went mainstream. The Beatles and The Monkees were quick to adopt the look in the 60s with matching Nehru jackets which is a collarless jacket that had its origins in India. As is the way, mainstream acceptance proved to be the death knell for the Mods. It gave way to the psychedelic hippie counterculture which largely rejected the suit.

The Revitalisation of Savile Row

Although Savile Row is known for its traditional bespoke tailoring, it is not entirely impervious to the wider popular cultural shifts in fashion, as well see shortly. Savile Row tailoring is seen as timeless and classic and, it is argued by some, should not be distracted by the transient tastes of fashion. However, if a customer requires suit cut in a manner that reflects current tastes, think Daniel Craig’s tight-fitting Tom Ford suit in James Bond, a tailor will acquiesce – if only partly. This interaction, these uncomfortable acknowledgements to the fashion will have an effect on house style, but not detrimentally. Meyer & Mortimer started out as military tailors, and this is reflected today in the suits we make.

The Meyer & Mortimer house style

Two Savile Row individuals who actively embraced popular culture, and in doing so revived bespoke tailoring, were Tommy Nutter & Edward Sexton. Considered to be the modernisers of Savile Row they came together to open a new shop called Nutters at Savile Row (at No.35). The business was an immediate success, mainly due to the networking prowess of its founders and some rather astute financial backing from members of music industry. It meant that the likes of Elton John, Mick Jagger, and The Beatles were now seen on Savile Row. Nutter is said to be most proud of dressing three of the Beatles for the cover of Abbey Road. George Harrison opted for double denim.

M&M Director Paul Munday with his old boss & mentor, Edward Sexton

Although they did not drastically alter the shape and cut of the suit, (their house style included a waisted and flared jacket with wide lapels and parallel trousers) their impact on bespoke tailoring was immense. Not only did they put Savile Row on the fashion map of London, alongside Carnaby Street and the King’s Road, but they also brought in younger and hipper customer which revitalised the industry.

Due to the longevity of the suit, it is no surprise then that earlier versions should reappear. The 1980s saw a return to broader, roomier suits, as we saw in the 1930s Yet this time, lines were sharper and shoulders more aggressively padded. Capitalism was the church and success and extravagance were its prayers. Waistcoats all but disappeared, the suit jacket waistline dropped below the natural waist, and single and double-breasted two-piece suits were the essentials for power-dressing.

Yours truly in my M&M three-piece suit

The 1980s could be considered the last decade or era to have any significant impact on the suit. Since then, it has gone through changes in cut but not to the extent seen then. Developments now appear to be subtler with the current trend being, whether one likes it or not, a tighter fitting suit. Like everything, this will pass and something new or old will take its place.

If anything, it shows the strength and enduring presence of the lounge suit despite the threats from fashion (real or not) and the phenomenon of dressing down. A suit has a language and vocabulary all of its own which other garments cannot replicate. Moreover, it allows space for the individual and their personality to come through. For these reasons alone the suit is here to stay for many more centuries to come.

M&M