To celebrate the launch of our new made-to-measure range of suits, we thought we would look into the history of the lounge suit. Also known as a business suit, it comprises of a jacket, trousers and for the three-piece, a waistcoat. It is an ensemble found in most men’s wardrobes. Some of us, like ourselves, who work in bespoke tailoring, will wear one daily; others, intermittently coming out for weddings, interviews or other notable occasions.

We are not going to focus entirely on the style changes themselves but more on the factors that determined these changes. To study developments in fashion, one must also contemplate history, politics, society and the input of two individuals.

Setting the standard, Charles II

The first of which, is Charles II (1630-1685), who in 1666 set the sartorial standard by decreeing English court men should wear a long coat, a petticoat (a waistcoat), a cravat (a precursor to the necktie) and breeches. Diarist Samual Pepys noted at the time “the King hath yesterday in council declared his resolution of setting a fashion for clothes which he will never alter. It will be a vest; I know not well how”. Fashion scholars argue that Charles II was not only instrumental in bringing together the three-piece ensemble but also responsible for inventing the waistcoat.

Where Did Charles II Get His Sense of style?

Historians believe his fondness for fashion was informed by two factors: his parents and his time in exile. Being heir to the throne, he was dressed in his father’s image (Charles I) from a young age, plus, his mother, Henrietta Maria, was French hailing from Paris. The accepted view is she brought her sense of (Parisian) style back to England which profoundly influenced her son.

The second factor is Charles’ exile from England. Maria Hayward writing in the journal Dressing Charles II says ‘He experienced court life in France, Scotland, the Spanish Netherlands and the United Provinces, as well as a number of cities in the Holy Roman Empire including Aachen, Cologne and Spa’. This exposure to a vast array of continental styles would have further shaped his sense of style. Once back on the throne in England, he was able to develop these ideas leading to the announcement in 1666 and arguably the birth of the three-piece suit.

Charles II dressing for the occasion (receiving a pineapple) in 1675

The Original Dandy & Hipster Beau Brummell

The other notable individual is the original dandy Beau Brummell (1778-1840). During the Regency (and wider Georgian) period he famously rejected frills, frocks and powdered wigs in favour of a simple jacket and long tight trousers. By doing so, he introduced the idea of a more uncomplicated men’s suit to the world.

Beau Brummell

Brummell was ex-military and good friend to the Prince Regent and future monarch, King George IV (who happens to be an old Meyer & Mortimer customer). In the army, Brummell had to pay for his uniform (along with a horse) so would have been familiar with visits to a tailor. In fact, most high ranking officers – of which Brummell was one – would visit a street in central London making a name for itself in tailoring excellence called Savile Row. Carren Jao, writing for the Smithsonian website, says ‘The tailors of Savile Row painstakingly built each uniform by hand. Patterns were chalked out on paper and then cloth, only to be adjusted again and again through multiple fittings, until a perfect fit was achieved’. Officers like Brummell would return to Savile Row for their civilian attire, and it is here that Brummell, along with his tailor, helped transition men’s tailoring from a military focus to civilian.

“Bedford, do you call this thing a coat?”

After leaving the military, Beau Brummell embraced London society and became preoccupied with clothes, gambling and developing a dry and cutting wit. An example of the latter is on meeting the Duke of Bedford, who would be his superior, at a social event. Brummell, who had been studying the Grace’s coat, took the lapel between his thumb and finger and wryly asked “Bedford, do you call this thing a coat?”

This Charming Man: Brummell wearing his creation

Brummell reacted to the then colourful ostentatious frills of men’s fashion by electing instead on perfection of cut, quality of cloth and conservatively dark colour schemes. With Brummell front and centre in London’s social scene his influence, along with his friendship with the Prince regent, was considerable. As a result, the jacket and tight trouser combination took off. Like Charles II earlier Brummell was an instrumental figure in adapting and imprinting his sense of style on the three-piece suit which is still evident today. Unfortunately, for Brummell, he spectacularly fell from grace due to a combination of wildly escalating debts and falling out of favour with the Prince Regent. Beau was a man who lived way beyond his means which eventually caught up with him. He fled the threat of debtors prison to Caen in France where he lived in poverty finally dying of syphilis at 61.

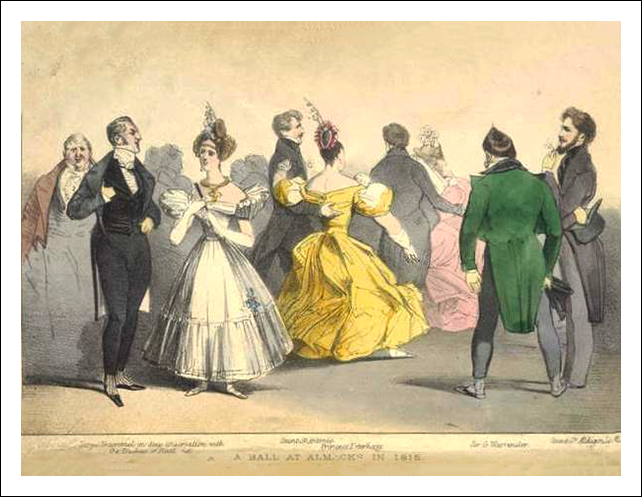

Happier times: Beau Brummell in deep conversation with the Duchess of Rutland*

At the same time Brummell was revolutionising men’s fashion another enormous shift was taking place with the Industrial Revolution. The textile industry benefitted hugely from new machine production methods. It also saw the introduction and proliferation of the sewing machine which made clothes more affordable and available to the masses. The Industrial Revolution also created the businessman who needed to address accordingly. Timothy Long, the fashion curator at The London Museum, says the businessman needed to ‘convey a sense of respectability and productivity and due to this, the suit becomes quite sober, void of any embellishments and always in black’.

The Industrial Revolution's Impact on the Men's Suit

Brunel preparing the launch of 'The Great Eastern

The Industrial Revolution spanned both Georgian and Victorian eras with prosperity benefiting the middle classes most of all. In this dawn of consumerism, this burgeoning class wanted to dress well and now had access to mass-produced garments. Where colour and overly elaborate design adorned women, men’s fashion on the other hand, as pointed out by Timothy Long, was dark and austere in nature. However, colour still managed to find a place in brilliantly patterned waistcoats (a nod to Charles II maybe) and cummerbunds along with smoking jackets and dressing gowns.

American smoking jacket circa 1860 courtesy of The Met Museum

In the Victorian era, men wore tight-fitting calf-length frock coats; waistcoats - which were single or double-breasted, and trousers with fly fronts. However, frock coats, along with morning coats (aka dress coat with tails) were not considered technically to be a suit as colour or fabric used did not match the trousers. Frock coats though were still the standard for business and formal occasions, and dress coats (with tails) for the evening.

The 1850s welcomed the introduction of shirts with upstanding or turned over collars. Also, the necktie became wider and was looped or tied and fastened with a stickpin. In the 1860s, frock coats got shorter to knee length. With the increase in outdoor activities among the middle and upper classes, the lounge suit increased in popularity as an alternative to its more formal relation. The tale disappeared from the back of the jacket, primarily down to the creation of the smoking jacket, which in turn helped create the dinner jacket or tuxedo.

To be continued...

30th April 2018: The second instalment is now published here The History of the Suit Part II.